The Unquiet Man

THE UNQUIET MAN

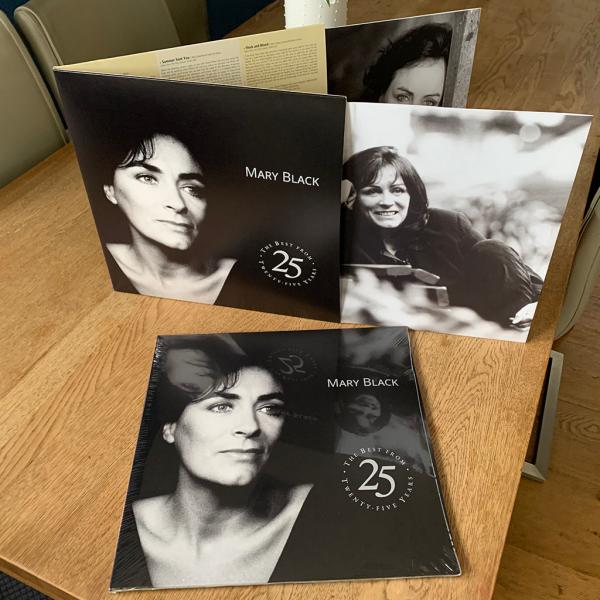

He's the historic link between Horslips, Moving Hearts, Mary Black and Sinead Lohan. His story sheds light on some of the most fascinating personalities and pivotal moments in Irish music. And after 25 years of letting his fingers do the talking he's not about to mince his words. He's DECLAN SINNOTT and he's telling all to JOE JACKSON.

Horslips. Moving Hearts. Mary Black. Sinead Lohan. Four names that span the history of Irish rock - and what do they have in common? The Quiet Man: Declan Sinnott guitarist, arranger, producer and soon-to-be recording artist in his own right. Though maybe Sinnott could be better described as "The Invisible Man" or a perfect replacement for any one of the Shadows.

Certainly he has remained in the background of the Irish music industry for at least the last quarter-century, preferring to allow his music to speak on his behalf, rarely, for example, participating in interviews. More than this, he once wrote a letter to HOT PRESS indicating precisely why he felt it would be totally unnecessary to pry into the private life of Mary Black for an upcoming interview, claiming that "the music should be what matters most of all", or words to that effect.

Thankfully, Sinnott is no longer such a purist and now realises that the emotional texture of a person's private life often shapes the core nature of the music, though he did ask for the tape recorder to be turned off at one point, when questioned about the recent break-up of his marriage. Nevertheless, Sinnott obviously feels it is about time he put on-the-record his own hitherto private views on the personalities involved in, and the music he made with, groups such as Horslips and Moving Hearts.

So sit back and relish this peripheral perspective on Irish rock. And try to remember that figures on the periphery often have a more revealing story to tell than those pivotal people whose tales have already been told a thousand times. Ladies and gentlemen, Declan Sinnott.

Joe Jackson: Firstly, why has it taken you so long to gig on your own, to even begin recording your own album? Many people would say it's about bloody time you moved into the spotlight.

DECLAN SINNOTT: People have been saying that to me for years! But I've had a huge block about it all my life. To be totally honest with you, I lacked confidence, always thought, "who'd want to listen to what I do on my own"? I've always been carefully tucked behind someone else, on stage, in the studio. That was my choice. Partly because of a lack of confidence and partly because, since Horslips in fact, I realised I seem to be more of an arranger. People kept saying, "how did you get those guys to sound like that?" and I said to myself, "that must be an arrangement I'm doing". So that became my life.

Joe Jackson: So it's you we've to bless, or blame, for the arrangements on those early Horslips recordings - the songs that gave the world "Celtic Rock"?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Well, I remember way back we were doing a weekly television show and had a huge row because they said, "you've arranged all the stuff so far, this week we're going to do it." But by the Friday before the programme nothing had happened so they said, "alright, you do the arrangements". That's when I really realised I had an ability to be more than a guitar player.

Joe Jackson: Flashing back even further than that, you had, apparently, felt like you were virtually reborn the day you first picked up a guitar in your early teens.

DECLAN SINNOTT: That's true. I didn't have a great childhood and the guitar was a kind of tunnel out of that, another emotional place I could go to, an addiction that wasn't destructive. And at the centre of all that was The Beatles, who I remember listening to all the time on the BBC. For many people of my generation, that too was like being reborn. It's like one day I was talking to somebody, and, suddenly, we were all Beatles fans! We wanted to know where they lived, what they listened to, what instruments they played. Everything about them fascinated us. Before that, I'd been into Elvis and loved things like 'It's Now Or Never' which was a kind of outlaw music. I remember my dad turning off the radio when that came on! It was considered shocking, because of the sexual connotations in "Be mine tonight"! In fact, it was banned in Ireland, because of that "tomorrow may be too late" line, which meant like, "let's have sex now." But, as I say, that made the music all the more exciting to me. Particularly because my dad hated it.

Joe Jackson: Was there anything about Irish music you liked at the time?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Some of the showbands, which, I know is really an uncool thing to say! But when you're a guitar player all you think is, "jeez, that's a great chord that guy played there." Like, I'd go to the parish hall and see somebody do a copy of a Beatles song and I'd think "that is as good as The Beatles!" I lived in Wexford and loved going to see the Greenbeats and The Freshmen. To us, they were brilliant. But, in terms of Irish music itself, I didn't connect with that until much later. As in, say, learning more traditional songs than ever before when I went to work with Mary Black.

But she was wrong to say she introduced me to acoustic music. The acoustic thing I was into since Dylan's John Wesley Harding which had a huge influence on me in '67, '68. That made me realise that acoustic guitar, acoustic drums and electric bass was the perfect combination. And Dylan stole that idea from Gordon Lightfoot, he admits. I was also a big fan of The Band, because of their let's-get-back-to-basics earthy approach to music. All that is what really formed my base. Especially with Mary, when I wanted it to be acoustic but not traditional. And that is what we achieved, certainly by the time we got to By The Time It Gets Dark, which I consider to be the first real album.

Joe Jackson: But, back when you were part of your first group, Tara Telephone with Eamon Carr, what kind of idea was behind that music? You, apparently, would play guitar while Eamon read his poetry and this later led to Horslips.

DECLAN SINNOTT: The idea was more where music and poetry would meet. Apart from Eamon's poetry, Peter Fallon gave readings and I'd compose the music and we'd play in Sinnotts, in King Street. It was an extension of the Liverpool poets, Iike Mike McGear, Beats like Ginsberg and an attempt to be more classical than all that. But we also composed songs and that did lead to Horslips. But it wasn't as easy as that sounds. Like, I remember, when I first moved to Dublin I was sleeping rough, didn't even have a place to stay. My parents had told me to get a "proper" job and I'd tried but it didn't work, so I just left home, at 19. Yet, as I say, life at home was oppressive. My father was a violent alcoholic, which was part of what I needed to escape from, through music. So Dublin definitely was an escape from all that.

Joe Jackson: Back home in Wexford, apart from that darkness at home, did you have girl-friends, sexual encounters, all that normal adolescent stuff?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Girlfriends were secondary to the music, always. I needed to have girlfriends and sexual contact but I needed music far more, even from my mid-teens. You'd go with a woman, okay, but when that was done you'd get back to the music.

Joe Jackson: So, where some guys reach for a cigarette after sex, you'd reach for the guitar?

DECLAN SINNOTT: And the cigarette!

Joe Jackson: Do you agree then with whoever said, "A woman never felt as good in my arms as a guitar"?

DECLAN SINNOTT: I did, but no longer. Or, at least, I battle with that feeling. Music is definitely my main obsession, far more than anything else.

Joe Jackson: Is that an emotional failing on your behalf? Have you been accused of this by women?

DECLAN SINNOTT: It is, yeah. And I have been. But if I could solve this problem maybe I'd solve all the problems in my life. Yet I don't regret making that choice. Where would I be, what would I be doing, if I wasn't playing music?

Joe Jackson: Drinking? Could you have become an alcoholic?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yeah. I was, for a while.

Joe Jackson: Is that what caused what you once described, in HOT PRESS, as the "health problem" that took you away for a year when you were working with Mary?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yeah. I left Moving Hearts for similar reasons. There were lots of reasons there, but I was falling apart, drinking huge amounts of brandy.

Joe Jackson: But if your father's alcoholism caused so much grief for your family, why didn't you see his ghost and draw back from such excesses?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Because that's the kind of logical link you make after the event. At the time I was way out on a limb, emotionally and psychologically. And the drinking didn't really become serious until I was in Moving Hearts. But I managed to give up alcohol and now I drink again, within reason, and don't have a problem anymore. Something inside fell into place, I don't need to be drunk anymore.

Yet I've only turned things around relatively recently. Being with Mary was really interesting and that allowed me to stay there far longer than I would have stayed with anyone else. She was great, the band was great and the money was great so that gave me a centre. But it was artificial because I was still avoiding doing what I knew I really wanted to do. I was frustrated at that level. Especially when we'd have to go on yet another tour, playing the same songs. That was definitely not interesting to me. You'd record an album, then spend two years touring it. So I became very stiff, an unyielding kind of character. I'd just go to my room after a gig, because there was nowhere else to go. I cut out drink but found no other way out. It was a very dark period in my life. In fact, the last two years has been pretty volatile in my life. Only now do I feel I've arrived at a point I never managed to reach in my life.

Joe Jackson: Okay, back to Horslips. You have previously indicated that you were "pissed off" with Horslips, feel they are overrated.

DECLAN SINNOTT: I do. From the start, as Tara Telephone, we were a bunch of guys doing something that was really esoteric and interesting. It was the same when Horslips began but then it got into, "You have to wear this shiny suit", we have to sing this, play that and, to me, it soon fell apart.

Joe Jackson: But who was dictating those terms?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Everybody was in agreement, basically, except me. But then I was taking more drugs than everybody else, listening to more Pink Floyd, or whatever. I was into being "real" and reckoned the compromises Horslips wanted to make were unnecessary, that they would lose credibility. They started out with far more credibility than they had a year and a half later. By that stage they suddenly became - well, we'd done an ad for an orange drink, for God's sake! What more can I say? And put on those shiny suits.

As such, our credibility really was going down. We definitely were getting slagged by rock bands who'd worked harder than we did. But then we were more successful than most of them so we didn't even bother to fight back. We realised that although they nearly all had better rhythm sections than ours, we had better ideas. But we definitely had the worst rhythm section in the world. Jesus, we were awful! But our ideas were good because they were not derivative.

Joe Jackson: Do you agree with music historians who suggest that what made Horslips unique was this rock-based rhythm section - irrespective of how crap it was -allied to the band's unpatronising view of Irish music and its attempt to blend the two?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No! Because that sounds like it was a decision that was made! What actually happened was that we tried to be a rock band but we were so bad we had to do something else. History should be more truthful. But very often in bands people say "oh, okay, I'll go along with what everyone else is saying." Especially with what critics say!

Joe Jackson: So do you go along with the claim that the single 'Johnny's Wedding' created "Celtic Rock"?

DECLAN SINNOTT: What Fairport Convention were doing before us, was that not "Celtic Rock"? Maybe it wasn't. (pause) Okay, 'Johnny's Wedding' probably was the first.

Joe Jackson: And it did open up people's eyes to the possibilities of blending rock and Irish music.

DECLAN SINNOTT: Definitely. Everybody began doing it! We'd be touring and see a van with a shamrock on it and say, "Jaysus, another one." Mushroom, Reform and maybe even Eyeless with Niall Stokes! In fact, Eyeless supported Horslips at one point. Indeed, I remember a gig where Eyeless played before Horslips and when their set was over, Niall's brother Dermot stayed at the piano and refused to leave the stage! He kept playing after the band had left the stage. So Horslips' manager said, "look, we have to go on" so we pushed the piano into the wings and Dermot just stayed there on the stool! But then we had no choice other than to come back for Eamon's stool ! And we did.

Joe Jackson: So, overall, did you see all "Celtic Rock" as a sham? Shamrock, sham-Celtic?

DECLAN SINNOTT: A lot of it, yeah. And I remember saying to Eamon Carr one day, "we'll be found out"! (laughs) That's really how I felt about it. And as a guitar player, trying to play over that rhythm section was a joke. It was, as I say, a bad rhythm section!

Joe Jackson: But before you jumped ship you did arrange, for example, all the material on the first Horslips album.

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yeah and I made a deal with them that I would not claim for the arrangements if they gave me, I think it was £150. I didn't know they were going to sell so many records.

Joe Jackson But when you listen to their entire recorded output do you accept that the rhythm section got better and the band evolved?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Two things happened. The band did get better but their ideas got worse! The Man Who Built America probably sounds more efficient than the first album, but it represents the point at which they left Irish music and decided to be a pop group. By that stage they weren't interested in innovation as much as "let's sell records." That's why I really never saw Horslips as all that great. Their ideas, originally, were good, but they were never fully realised.

Joe Jackson: Do you still talk to the other guys from Horslips?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Some of them I haven't spoken to since then. Barry Devlin I haven't spoken to. But l've spoken to Eamon and jimmy. I haven't really seen Charles. Yet the point is that I was angry for a long time and I think that when I was part of Horslips they saw me as a little shit. Because I was the youngest and taking the most drugs.

Joe Jackson: Does that mean you were fucking things up for them? At gigs, and recording?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Quite possibly, but not often. I remember one gig i fucked up for them.

Joe Jackson: But if they were taking drugs too they can't play the "Holy Joe" role in this, can they?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No. But I was more serious about drugs!

Joe Jackson: As in what?

DECLAN SINNOTT: LSD, smoking, mostly. And anything else anybody'd have. Purple pills, green, blue. I really felt we were on a spiritual journey, as did a lot of people at the time. It really wasn't pleasure-seeking as much as that. And there was something happening at that time, along these lines. So when I hear people criticising kids for using Ecstasy at raves I say, "this is the nearest these kids get to going to mass". And I did get a strong sense of spiritual growth from using drugs. just being able to see into your own psyche and see into the psyche of somebody else and knowing you're connecting at that level.

Joe Jackson: But were you really connecting with whoever was doing drugs with you. Or even connecting with "God"? Or was it all like the kind of cocaine delusion that leads people to believe they are God?

DECLAN SINNOTT: I believe I was connecting. Definitely. Even though I don't believe in Cod, in any strict Catholic sense. And in terms of personal relationships it did often help, though, yes, it also was, of course, dangerous. I certainly had a few bad experiences where you'd be terrified, wondering were you ever going to get out of the trip. But it wasn't so much the drugs that led me away from Horslips, it was more that I really was less interested than they were in simply success and so I started listening to people like Stephen Stills, wanted to move along those lines. That bluesy stuff seemed more authentic to me than "Celtic Rock".

I also felt that as a musician I was becoming less of a craftsman in Horslips, that anything'd do as long as it got acclaim. In fact the first time I really felt like a guitar player was a couple of years later when I was playing in pubs as part of Candydancer, with a friend of mine called Tony Henderson. That only lasted nine months but it was so uplifting after all the other shit, so much "let's just play music". It was great. We didn't have that "we need to make it" scenario and that suited me fine.

Joe Jackson: But how did you live?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Very badly! On the dole. But that didn't matter so much to me then because I didn't have the responsibilities I have today.

Joe Jackson: So, what about Moving Hearts? Do you think they're worthy of all the critical acclaim they receive in relation to blending rock, traditional and jazz musical influences?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yes, definitely. Musically, Moving Hearts were a great band, a magical combination. But it didn't have any pop music sensibility. That's the one thing it lacked. l remember Brush Shiels being on the radio once and saying, "Horslips were too far in one direction because they couldn't really play and Moving Hearts were too far in the other direction, they should have been somewhere in the middle." l agree with that. But I felt good about my input into Moving Hearts, even though Donal Lunny was regarded as more of the arranger than I was. Though I did write three of the instrumentals on the first album, with Donal. And I helped to write things with Mick Hanly, which was a great learning experience.

Joe Jackson: Was Moving Hearts a band that moved according to a "thought-out" plan or, like Horslips, did they fall into things more by accident?

DECLAN SINNOTT: It was meant to be "thought-out" but more often than not we did fall into things by accident. Christy and Donal had originally come over to my flat and said, "we're thinking of starting a band and doing something different" so we did start it all. The name was even my suggestion, as the opposite to Talking Heads. They were fairly intellectual, arty American rock, whereas Moving Hearts was more emotionally based.

And I'll tell you, when we went in front of audiences for those early gigs, it was brilliant. We knew we had something special to offer. Part of it, for me, was the improvisatory aspect, like my work on 'No Time For Love'. In that sense, it was fucking great playing live with Moving Hearts. But once the first album was made and got all that acclaim things changed, for me. And even so, that first album wasn't as good as it could have been. The recording business in Ireland hadn't developed to the level where we could get things to sound the way we wanted them to sound. The Storm sounds better. The problem was that engineers would clean up sounds, whereas what matters, to me, is getting the noise a musician hears in their heads onto a tape. That's why I really do feel that the early Moving Hearts gigs were much better than the first album.

Moving Hearts did a live album later, but to me, if the white heat of the early Baggot Inn gigs had ever been captured by somebody who really knew how to record a live band that would be the recording l'd want us to be judged on. I remember one gig in Limerick where, when we came on stage and started our first number, the whole crowd just jumped back, because of the power of it all! In fact, I always thought that Moving Hearts was like a heart attack when we played live! At least that's how people responded to us. As if they all had a sudden Moving Heart attack! Either way, that whole experience was one of the high-lights of my life. We were fucking brilliant, at that point.

Joe Jackson: But why exactly?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Because we all had different perspectives on how the music should be and that dynamic made for a pretty tempestuous time! But the dynamic stopped working for me even when Christy was still in the band. The second album is nowhere near as good as the first. Despite the faults of that first album I felt we had nailed down all the areas of invention we could and that we couldn't go any further. After that there wasn't anything of significance that developed in Moving Hearts, There were inventions on the first album, like 'Hiroshima' which is a thing to itself. 'Irish Ways' too. A number of tracks. But nothing on the second album has that amount of creativity. The energy was depleted, we couldn't go forward. That's what I felt, instinctively. The central dynamic was gone. Once the seven of us got together the buzz only lasted about six months. It was over in my head long before I left the band.

Joe Jackson: But were you doing tons of drugs, drinking too much, expecting the music to create a surrogate buzz at that level? A quick "hit" rather than anything else?

DECLAN SINNOTT: But everybody was doing "fast" stuff, brandy and fast drugs. Not necessarily for the music but because they wanted to. And I felt like Moving Hearts was sucking up everyone's lives at that point, making life more difficult for all of us. We were all dragged into this huge excitement and lost our bearings, to a degree. But, at least, l got paid all the money I could have been paid, though the earnings still were relatively small.

Joe Jackson: Did you participate in that legendary Moving Hearts tour where the band had to go back on the road just to pay off debts?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No. I'd left before they ran up those debts. It was like £10,000 when I left but later got up as far as £70,000. I only did one gig after I left the band. And I regretted doing that because I'd had great memories of the band and didn't want to ruin that by going back there again. l wasn't psychologically dependent on Moving Hearts, like some band members were, which is also part of why they got back together. But, financially, we'd fucked up because we saw ourselves as a co-operative and record companies at the time simply didn't want to deal with musicians. They wanted a man in a suit who would talk their language.

Joe Jackson: Apparently, seeing Mary Black in a gig before you left Moving Hearts made you want to work with her because of what you once described as the emotional power in her voice.

DECLAN SINNOTT: That's true but I didn't see myself as her producer, at first. Christy suggested that. And suggested I play with her on an early gig. All that led to my producing her albums. But, for the first album, I was hanging on by my finger-nails, watching the engineer, trying to work out how the fuck a producer did things. And the second album we did, Without The Fanfare, I really didn't like. As I said earlier, it all only came together when we got to By The Time It Gets Dark. In terms of the choice of songs, the production, Mary's singing. It had a very limited emotional range, but, to me, everything on that album works perfectly. Everything. It's dark but beautiful. But then my own darkness is in there too. When Mary was singing some of those sad songs I was singing right alongside with her. Those two Johnny Duhan songs are heavy, but l can relate to them, easily.

Joe Jackson: If it's any consolation to you, I believe that By The lime It Gets Dark is one of the most sublime creations in Irish popular music. And one of my favourite memories of Leonard Cohen is seeing him walking down a corridor in Jury's Hotel, with a CD of By The Time It Gets Dark under his arm.

DECLAN SINNOTT: That seems quite fitting, doesn't it? That's great.

Joe Jackson: But let's get back to the question of engineers, who rarely get the credit they deserve. Is it true that Dan Fitzgerald's engineering wizardry on many Mary Black albums led to them winning awards from hi-fi equipment manufacturers and to them being used in hi-fl shops as test albums?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yeah. And Dan Fiizgerald has a great ear for sound. He's very fussy about mic positioning and all that and gets what he wants from a recording. And that really helps in my case because I tend to produce things that are sparse and want every instrument to be heard. So Dan's engineering and my clarity did make people use the albums for the reasons you mention. But then I Iike to be able to see right through the mix, to see every bit of what's happening, so that everything is understandable. At least, that was when I was working with Mary. Now, as a producer I'm beginning to think in broader terms, take on other concepts.

Joe Jackson: So, okay, tell me where, in all the recordings you've worked on, can I most clearly hear the voice of Declan Sinnott?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Maybe you won't until I make my own album. But that may not even be it. Maybe you only hear it when I play live. For example, I did a gig in Whelan's recently and that was a huge step forward for me. Because, though you were only joking about it earlier, for years I did feel like I was the invisible man of the Irish music industry. But being on stage I realised maybe I was wrong to only see myself that way. And that gig was an important statement, for me. Like saying, "here I am, I exist." But there are moments on the records I've done where maybe people will hear my own voice clearer than ever again. We'll see, when I record my own album. I make my living recording other people but I've got to record my own stuff, just once, just to see, for myself.

Joe Jackson: Do you still get a sense of self-gratification from producing someone like, say, Sinead Lohan?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Very much so.

Joe Jackson: But did you need to work with Sinead? The last time we talked you were still with Mary Black and seemed pissed off at Jackie Hayden saying that your work with her had become formulaic. Was that something about which you and Mary agreed, when you decided to leave her band?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No. It wasn't a mutual agreement, I just left. Partly because when I started working with Sinead I started using this system [points to bank of equipment in his own studio in Dublin's Temple Bar area]. Using midi, samples, live performances combined with synths and drum machines. So, when I was working with Sinead often nobody else was there, not even Sinead. We did her guide vocals at the beginning and the real vocals at the end but for an awful lot of the time I was in a room on my own and that's when Sinead's debut album was made. Whereas with Mary there was a band there, an engineer, all that. So part of the reason I left Mary was because I thought I could be more me working this way. As well as also spending less time in hotels, which, as I say, had become hell to me.

So when I recorded Sinead, I designed the studio myself, got all the gear, learned the technology and took it from there. It just got to a stage where I decided, "I have a few bob, I can record like that". In some projects I have people come in and record three tracks, don't charge them anything, then try and sell the project to a record company. I also am doing work with someone like Mick Hanly who, I feel, hasn't made a great record yet. I'm hoping he will make a record that really represents him. He's usually been forced to make a record in four days, ; which is crippling.

Joe Jackson: Did you make Sinead Lohan do anything on her album that was more a part of your musical vision than hers?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No. I went to extremes to avoid that. I was trying to remain subservient to her picture, though there is an awful lot of me in something like 'The Battle'. She would never have done that song that way were it not for the fact that, one night I got this rhythm going and she said "that's great." But she also had all these extra beats and bars in songs and though my initial response was, "I've got to change that", I didn't. I also didn't tell her how to sing on the record and though she doesn't play guitar, I very often took from what she had played and copied it.

Joe Jackson: So why doesn't Sinead play guitar on her own album?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Because she sounded very ineffective.

Joe Jackson: So it's your guitar lines we hear?

DECLAN SINNOTT: Yeah.

Joe Jackson: Yet you still wouldn't say what we hear is you imposing yourself on Sinead?

DECLAN SINNOTT: There's barely a guitar break on the album. So, no, there is no point at which I walk out to the front and say, "this is Declan Sinnott here." As much as possible, it was her album. And it was a hit, went platinum in Ireland.

Joe Jackson: Are you producing her next album?

DECLAN SINNOTT: No. But what I learned from doing her first album was that I can paint a picture without having to deal with all the compromises that being a member of a band entails, as in being with Mary's band. I know that may sound like it's my picture I'm talking about, but it's not. Not necessarily. And as for Mary, she's gone on to do an album with Larry Klein, Joni Mitchell's producer. I've only heard a few tracks but it sounds good and she's trying to be as different as possible.

Joe Jackson: Happily, because most critics - including myself - savagely attacked her last album, The Circus.

DECLAN SINNOTT: I was critical of it too. It was the end of it all for me. There was nothing going on there. We were more in disagreement about where that album should be going than about anything else, ever. But Larry Klein has the freedom to say, "no, I don't want to use", whatever, because he's not part of her band. I eventually came to the position where I just had to compromise in order to be able to live in the back of a van with these people. In that sense I stopped feeling like a producer, felt more like an accommodator. But when I started producing Sinead I felt liberated again. And there's another singer coming up that I'm really excited about, Tara Byrne. I'm working on her album. And by the time this interview appears in HOT PRESS, John Spillane, from Nomos, will have released his album, which I produced. It's called The Tree Of Stars. And as with Sinead, that's basically me and him together, though he stayed around for a lot of the time. And there are more players, like pipes and fiddle. So it's like a combination of a strong Irish influence on john's voice, with me in there somewhere. A little bit of me!

Joe Jackson: In the final analysis you really will have to make your own album, won't you?

DECLAN SINNOTT: I guess so. (laughs) But God knows when I'll finally finish my own album. Or even really get started on it! If I ever do.